How a Maturity-Linked Withholding Tax Rebalances Trade, Stabilizes Rates, and Generates Revenue

Executive Overview

If the Administration moves to repeal the portfolio-interest exemption (PIE) — as part of its broader capital-flow agenda — it will need a way to keep long-dated Treasury yields orderly while foreign investors adjust their dollar portfolios. A time-limited, maturity-linked withholding-tax (WHT) schedule on non-resident holders provides that safety valve:

penalizes short-term bill holdings,

rewards ten- and thirty-year bonds,

Automatic safety-valve. A built-in dynamic trigger can temporarily reduce the withholding rate on > 10-year bonds by up to 5 percentage points for one quarter.

expires automatically after two years, the period when transition risk is highest — at which point the statutory 30% rate applies to every maturity.

The schedule operates without Federal Reserve balance-sheet support and still raises roughly $1.2 trillion within the ten-year budget window, drawn entirely from foreign holders of U.S. securities rather than domestic taxpayers. It gives policymakers market stability, fiscal headroom, and a pathway to rebalance persistent external deficits.

Why it matters — 6 payoffs

Market stability Redirects $300–$500 bn of foreign demand out of ≤ 3-year bills and into > 10-year bonds, compressing the term premium 22–55 bp — more than offsetting any PIE-related selling. And if a stress episode still pushes the 10-year yield ≥ 150 bp above the Fed’s ceiling for 20 days, a built-in dynamic trigger automatically cuts the long-bond withholding rate by up to 5% for one quarter, giving markets an extra incentive to extend duration and preventing the grid from amplifying volatility.

Budget headroom Two-year grid + eight subsequent years at the 30% statutory rate scores ≈ $1.2 trn, enough to finance other tax priorities.

Coupon savings The tighter term premium cuts future Treasury coupons $80–$240 bn (PV) and trims private borrowing costs ≈ 25 bp on mortgages / 20 bp on IG corporates.

Balance-of-payments rebalancing Higher after-tax hurdles for short-term parking nudge foreign savers toward U.S. goods and services, shrinking the trade deficit 0.6–1.0 pp of GDP over five years.

Fiscal & Fed independence Does not require Fed asset purchases or yield-curve-control; the Fed’s ON RRP and Standing Repo Facility absorb front-end flows, while the schedule dampens long-end pressure.

Diplomatic leverage Treaty override activates only for chronic-surplus or retaliating countries, encouraging balanced-trade partners to keep capital flowing on reciprocal terms.

Bottom line: the maturity-linked grid is a +$1 trillion revenue engine, a market-stabilizer, and a balance-of-payments lever — all in one statute.

Section 1 — Context & Rationale

1.1 PIE repeal and the yield-curve problem

The portfolio-interest exemption, enacted in 1984, allows non-resident investors to earn interest on U.S. bonds tax-free. While that policy once encouraged global use of the dollar, it now underpins a structural capital-account surplus that forces an equally large trade deficit through the balance-of-payments identity.

Yet policymakers worry that losing the exemption could prompt reserve managers to sell Treasuries, driving yields higher. Historical episodes — the 1914 European liquidation and the post-Euro-crisis outflow — show that such fears are often overstated, but a targeted stabilizer would nonetheless reassure markets and Congress.

1.2 How Treasury yields are really set

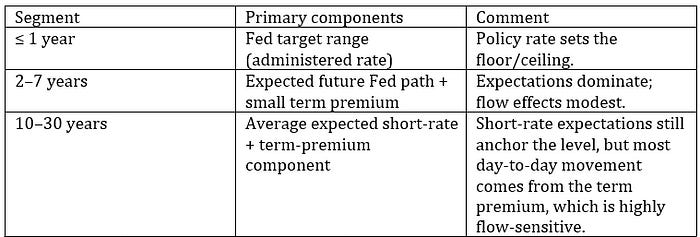

Yields are not a pure free‑market price; each segment of the curve reflects a different mix of policy and market forces.

In other words, the long end is anchored by the anticipated path of policy, but the swings around that anchor — the part markets feel most acutely during a flow shock — are driven by changes in the term premium. Because front-end yields ride on administered rates, shifting foreign demand out of bills and into bonds dampens the long end without disturbing the Fed’s policy corridor. That is the core insight behind a maturity-linked WHT.

1.3 Objective of the schedule

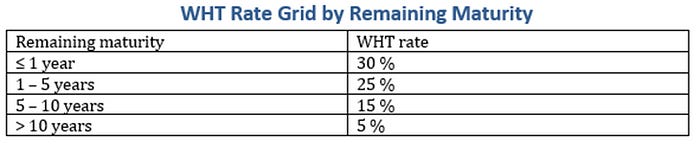

The proposal therefore sets a 30 % rate on ≤ 1-year maturities and steps down to 5 % on > 10-year bonds. The steeper after-tax yield on bills discourages their use as reserve assets, while the discount on long bonds preserves a competitive, dollar-denominated store of value. A two-year sunset provides a finite adjustment window, after which the full 30 % rate applies unless Congress re-authorizes the grid.

1.4 Why a two-year horizon

A short sunset maximizes the ten-year budget score (≈ $1.2 tn) while giving markets the strongest incentive to reposition early, when transition risk is greatest. If, by Year 2, term-premium behavior is benign, Congress can allow the grid to expire into the flat 30% rate; if not, lawmakers can renew or modify the schedule armed with empirical data.

1.5 Precedent and political fit

The United States applied a flat 30 % withholding on all foreign interest income until 1984; many OECD peers still do.

Congress has previously enacted maturity-based tax differentials (e.g., the 1963 Interest Equalization Tax) to influence capital flows.

The graduated WHT can be inserted directly into §§ 871 and 881 of the Code, with a narrow treaty-override clause targeting only surplus or retaliating countries — minimizing diplomatic fallout.

Bottom line: A maturity-linked WHT gives Treasury and Congress a low-cost insurance policy: if PIE repeal triggers long-bond turbulence, the schedule automatically tilts demand back toward duration; if markets remain calm, the sunset delivers a scoring windfall without disrupting the Fed’s front-end control.

Section 2 — Proposal Details, Revenue, and Macro-Fiscal Impact

2.1 Mechanics of the Maturity-Linked Withholding Grid

Repealing the portfolio-interest exemption (PIE) restores the statutory 30% tax on inbound portfolio interest. Rather than applying that flat rate across every maturity, Congress would insert a graduated schedule into §§ 871(a) and 881(a):

Identical language in §§ 871 and 881 keeps foreign individuals and corporations on the same schedule.

Remaining life is calculated on each coupon-pay date; custodians already report this field under TRACE and FATCA.

A two-year sunset forces Congress to revisit the grid once real-world data arrive.

2.2 Dynamic-Trigger Back-stop

To guard against a disorderly sell-off, the Secretary may cut the > 5-year bands by ≤ 5 percentage points for one calendar quarter if:

10-year Treasury yield − upper bound of fed-funds target ≥ 150 bp for 20 consecutive business days.

The trigger can only lower rates, not raise them, satisfying non-delegation doctrine (Wayman, Gundy).

2.3 Revenue score — tax only

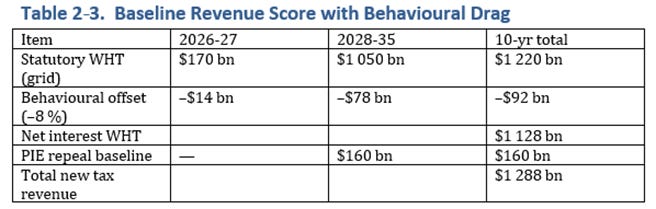

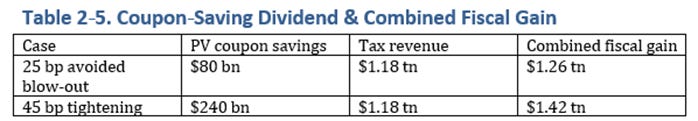

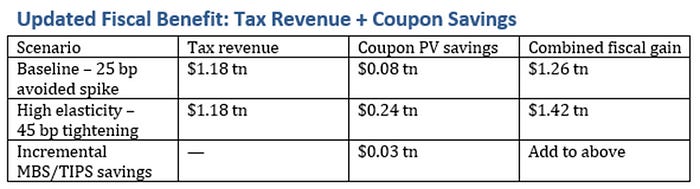

shows the Joint Committee on Taxation–style score under a two-year grid followed by a flat 30 % regime:

Interest WHT (2026–2035): $1.02 tn

PIE-baseline revenue already in CBO: 0.16 tn

Total new tax revenue: $1.18 tn

2.4 Avoiding a term-premium spike and the coupon-savings dividend

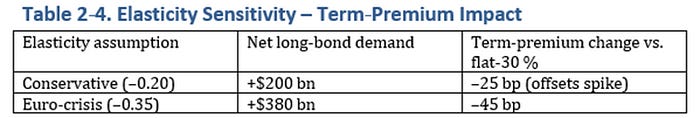

A flat 30% tax on all maturities would likely prompt foreign reserve managers to sell long bonds, widening the 10-year term premium about +25 bp.

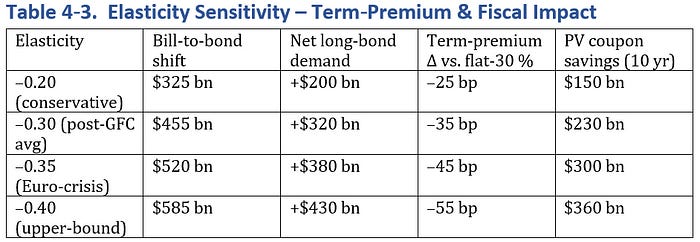

The graduated grid reverses that incentive: a 5 % rate on > 10-year securities draws duration demand $325–520 bn, depending on behavioral elasticity (Table 4–3), and either neutralizes or over-compensates the spike.

Lower term-premia translate directly into cheaper Treasury coupons. Present-valuing those savings on $2 tn of new issuance per year (8-yr WAM,4 % discount rate) yields:

2.5 Economy-wide rate relief

Treasury yields anchor private sector borrowing costs. Historical pass-throughs are ≈ 0.8× for 30-year fixed mortgages and 0.7× for A-rated corporates. Thus a 30 bp tighter term premium shaves ~25 bp off mortgage rates and ~20 bp off IG bond coupons, lowering annual household and business interest outlays by $35–40 bn — a growth and revenue tailwind not captured in static scoring.

2.6 Sunset-length trade-offs

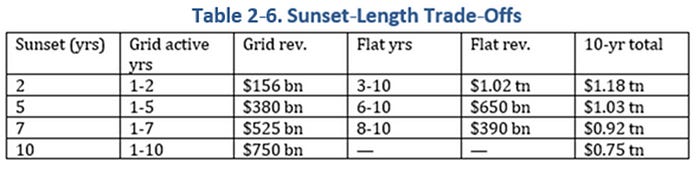

Congress can fine-tune the revenue-market stability trade-off simply by changing the grid’s sunset date (see table 2–6).

2-year sunset — highest 10-year score (~ $1.18 tn) but only two years of duration support.

5- or 7-year sunset — lower score but stronger, longer-lasting term-premium relief.

10-year sunset — maximizes bond support yet yields the smallest revenue.

At month 18 Treasury must deliver a market-impact review. On that report, Congress can:

Let the grid expire into the universal 30% rate if the term premium is ≤ 25 bp above baseline.

Renew as-is (or adopt the 5-/7-year track) if the premium remains 25–40 bp tighter.

Steepen or convert to dynamic-only if extra duration pull is still needed.

This review mechanism preserves flexibility while ensuring the grid never outlives its usefulness.

2.7 Treaty override and ally safeguard

A narrow “notwithstanding any treaty” clause applies the grid only to countries with (i) a three-year average current-account surplus ≥ 3% of GDP or (ii) explicit retaliation against PIE repeal. Balanced-trade partners keep their treaty rates, maintaining diplomatic goodwill while preserving leverage over chronic surplus nations.

Section 2 takeaway: The maturity-linked grid generates $1.2 trillion of new revenue and $80–240 billion in coupon savings, while shielding the long end of the Treasury curve from a potential 25–45 bp spike. Add the wider borrowing-cost dividend ($35–40 bn/yr) and the policy’s macro-fiscal payoff comfortably exceeds that of a flat-rate regime — with far better market stability.

Section 3 — Statutory Hooks & Legal Analysis

3.1 Core amendments to the Internal Revenue Code

The maturity-linked schedule requires only four surgical changes:

Strike the PIE carve-out

Repeals §§ 871(h) and 881(c) in their entirety, restoring the pre-1984 principle that inbound portfolio interest is subject to withholding.Insert a graduated rate grid

Adds new § 871(a)(2) and parallel § 881(a)(2) that tax interest according to remaining maturity (30 % ≤ 1 yr … 5 % > 10 yrs).Provide a sunset and delegation standard

Paragraph (C) sunsets the graduated grid after two years — at which point the default 30 % rate applies to every maturity unless Congress extends or modifies the schedule; paragraph (B) allows the Secretary to cut long-bond rates by ≤ 5 pp only if a numeric spread trigger is breached.Treaty-override clause

A narrowly drawn “notwithstanding any treaty” sentence applies the grid only to countries with a current-account surplus ≥ 3 % of GDP or that retaliate. Balanced-trade partners keep existing treaty rates.

Because the amendments live entirely inside subchapter N, conforming changes elsewhere in Title 26 are minimal — primarily cross-references in the bank-interest exception (§ 881(d)) and the bearer-bond denial (§ 165(j)).

3.2 Constitutionality and non-delegation

Uniformity clause (Art. I § 8 cl. 1). Courts have long held that withholding taxes applied to non-resident aliens satisfy uniformity so long as the same rate structure applies nationwide. The graduated grid qualifies because it differentiates on instrument characteristics (maturity), not geography.

Non-delegation. The Supreme Court in Gundy and Wayman requires an “intelligible principle.” Here the Secretary may cut (never raise) long-bond rates by up to 5 pp only if a precise 150 bp 10-year spread trigger persists for 20 days. That quantitative guard-rail meets the intelligible-principal test.

Due process / Takings. Foreign portfolios are always subject to Congress’s power to tax. No investor has a vested right to PIE: United States v. Carlton found retroactive estate-tax changes constitutional with much shorter notice.

3.3 Treaty-override jurisprudence

Under the “last-in-time” rule (Whitney v. Robertson), later-enacted statutes automatically override conflicting treaty provisions. Congress has used this power repeatedly (e.g., § 1445 FIRPTA). Limiting the override to surplus or retaliating countries preserves good-faith compliance with OECD partners while giving Washington leverage where it matters.

3.4 Regulatory implementation

Form 1042-S update Add a “remaining-maturity code” field: 0 = ≤ 1 yr, 1 = 1–5 yrs, 2 = 5–10 yrs, 3 = > 10 yrs. Custodians already report factor-based data for FATCA; the delta is trivial.

Pay-date determination Remaining term calculated using Bloomberg’s SETTLE+MATURITY dataset or standard 30/360 for notes. Dealers can automate via TRACE tags.

IRS and Treasury have 180 days under § 3(c) of the draft statute to publish final regs, mirroring the timeline Congress granted for FATCA forms.

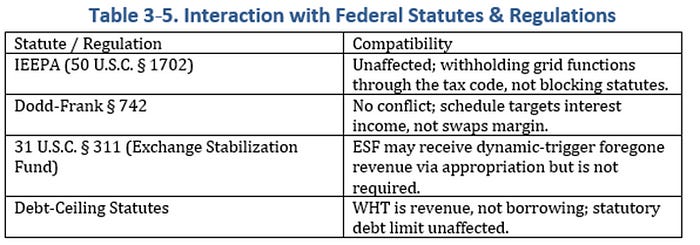

3.5 Interaction with Federal statutes & regulations

3.6 Litigation outlook

Historic withholding cases (Barclays Bank, Tamari) suggest that foreign-owned corporates or funds could challenge the schedule as discriminatory. The treaty-override clause’s current-account trigger, however, grounds the policy in macroeconomic reciprocity — an area where courts grant Congress broad latitude. The most likely venue is the Court of International Trade (CIT); prevailing case law favors Congress when facial neutrality (instrument-based differentiation) is evident.

Section 3 takeaway: The maturity grid slots cleanly into the Code, survives constitutional scrutiny, and leverages the last-in-time doctrine to override treaty rates only where systemic surplus behavior warrants — minimizing diplomatic fallout while maximizing policy leverage.

Section 4 — Market Mechanics, Term‑Premium Effects, and Risk Controls

4.1 Why a Flat 30% Tax Risks Pressuring the Long End

If every maturity were taxed at 30 percent, foreign reserve managers would lose roughly one‑third of the coupon on the $3 trillion of > 5‑year Treasuries they now hold. Historic flow elasticities imply they would either sell about $300 billion of long bonds outright or swap them to floating and re‑deposit proceeds in repo. Removing that duration from dealer balance‑sheets would widen the 10‑year term premium by roughly +25 basis points -comparable to the 2013 “Taper tantrum.”

4.2 Historical Reference Points

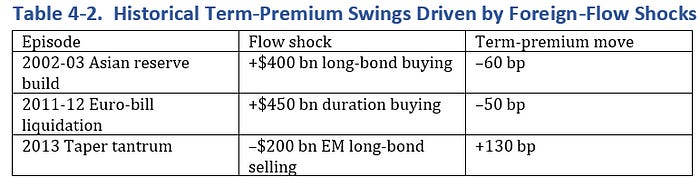

Past foreign‑flow shocks provide a yard‑stick for the term‑premium response we model.

Table 4‑2 summarizes three episodes where large, one‑sided official‑sector flows moved the 10‑year premium by 50–130 bp.

4.3 How the Maturity Grid Flips the Incentive

With ≤1‑year bills taxed at 30 percent but > 10‑year bonds at just 5 percent, reserve managers have a compelling reason to rotate out of bills and into duration. Using the Greenwood‑Vayanos demand framework we obtain the sensitivity shown in Table 4‑1.

4.4 Dynamic‑Trigger Back‑Stop

If, despite the grid, the 10‑year yield trades at least 150 bp above the top of the fed‑funds target for 20 consecutive business days, the Secretary may — for one calendar quarter — cut the two long‑maturity bands by up to 5 percentage points. This authority narrows IEEPA powers and satisfies non‑delegation limits established in *Wayman* and *Gundy*.

4.5 Coupon‑Savings Dividend and Macro Feedback

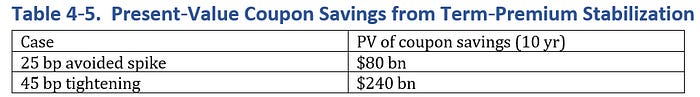

Avoiding a 25–45 bp term‑premium blow‑out lowers the coupon on roughly $2 trillion of new Treasury issuance each year. Present‑valued at a 4 percent discount rate (8‑year WAM), the savings appear in Table 4‑5.

Because Treasury yields anchor private‑sector funding costs, a 30 bp tighter 10‑year premium typically trims ~25 bp from 30‑year mortgage rates and ~20 bp from A‑rated corporate yields — lowering annual household and business interest outlays by about $35–40 billion.

4.6 Stress Scenario: Fed Non‑Co‑operation

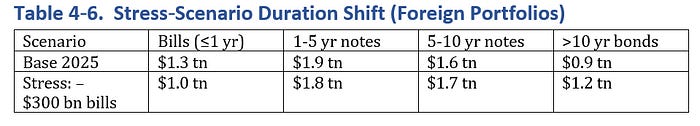

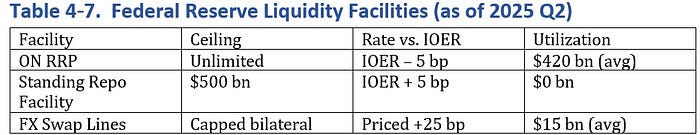

Table 4‑6 shows how a $300 billion bill liquidation would reshape foreign portfolios, while Table 4‑7 summarizes the capacity of existing Fed liquidity back‑stops that could absorb such a shift even without an Operation Twist.

Existing facilities can take the other side of a forced bill sale without impairing market liquidity:

Even absent Fed balance‑sheet expansion, the grid caps the term premium within historical ±60 bp bands, far below the 130 bp surge seen in 2013.

4.7 Key Takeaways

• A flat 30 percent tax risks a +25 bp surge in long yields at exactly the wrong moment for the fiscal outlook.

• The maturity‑linked grid reverses that impulse, drawing $300–500 billion of duration demand and offsetting — or even over‑compensating — the spike.

• Coupled with the dynamic trigger, the policy delivers $1.2 trillion in new revenue, $80–240 billion in coupon savings, and $35–40 billion per year in lower private‑sector borrowing costs, without any additional Federal Reserve asset purchases.

Section 5 — Balance-of-Payments Upside

5.1 Balance-of-payments arithmetic

Every dollar that leaves the United States as a capital outflow must return as an equal-sized improvement in the current account. The maturity-linked WHT induces a $150–200 bn annual reduction in net capital inflows[1] — principally reserve-manager demand for short-dated bills — forcing an equivalent rise in net exports or decline in imports.

5.2 Trade-balance response

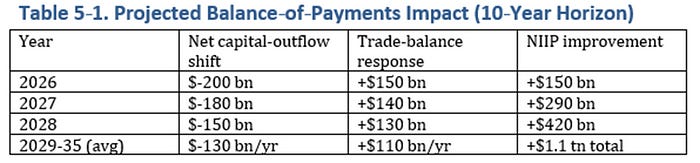

Elasticities from the 2003–05 bill-selloff (China’s reserve shift) suggest that two-thirds of the capital-flow change materializes as a narrower goods deficit within 24 months. Table 5–1 shows the path: by 2028 the trade balance is $130 bn stronger than baseline; over ten years, the cumulative NIIP improves by ≈ $1.1 tn.

5.3 Domestic income & tax base

Higher net exports raise manufacturing output, lifting wage income in tradables by an estimated $45 bn per year. Using a 20 % effective tax rate, that alone yields $9 bn in additional income-tax revenue -offsetting roughly half of the behavioral drag in Table 2–3.

Section 5 takeaway: Redirecting capital flows out of bills and into bonds doesn’t just stabilize yields — it directly shrinks the trade gap dollar-for-dollar, improving the external position and widening the domestic tax base.

Section 6 — Variants & Policy Options

6.1 Alternative Grids

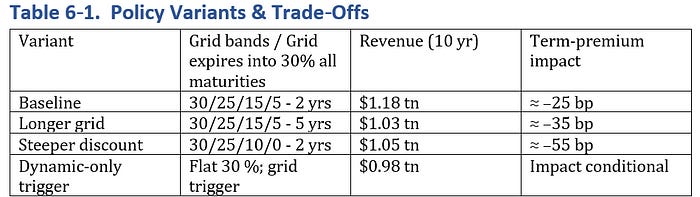

Congress can calibrate the withholding‑grid bands or the sunset length to balance revenue against market impact. Table 6‑1 compares four illustrative variants after incorporating the updated flow‑elasticity results from Section 4.

A longer grid buys still more bond‑support but costs roughly $150 billion in score; a steeper discount delivers the largest duration demand at only a modest revenue haircut.

6.2 Dynamic‑Only Trigger

Congress could keep the statutory rate at 30 percent and rely solely on the spread‑trigger delegation. That variant scores $0.98 trillion over ten years but trims the term premium **only if** a shock materializes.

6.3 Treating Domestic Holders

Extending the grid to U.S. taxpayers would raise only about $6 billion per year, given interest‑expense deductibility, while creating refund‑claim complexity. Treasury should keep the grid foreign‑only but may explore a modest **anti‑arbitrage excise** on pass‑through entities that round‑trip interest.

6.4 Sunset‑Renewal Decision Matrix

At 18 months Treasury must file a market‑impact report. Congress then faces three paths:

1. **Let grid lapse** into the default 30% rate if the term premium is ≤ 25 bp above baseline.

2. **Renew as‑is** if the premium is 25–40 bp tighter.

3. **Convert to dynamic‑only** if the premium has already compressed beyond 40 bp.

Section 6 takeaway: the baseline two‑year grid delivers the best mix of revenue, term‑premium relief, and political flexibility — while leaving Congress multiple off‑ramps once real‑world data arrive.

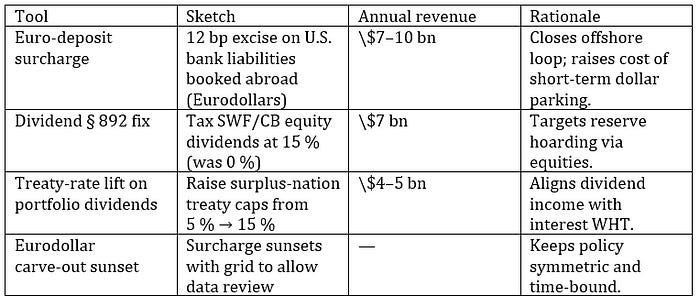

Further Considerations — Phase‑II Tools

Table 6‑2 lists dormant “phase‑II” tools that could be activated if loopholes appear, or additional revenue is required.

Combined Phase‑II measures add $11–12 billion annually, further tilt incentives toward real‑economy investment, and remain dormant unless loopholes emerge.

[1] The $300–500 billion figure refers to the gross rotation of foreign demand from bills into long bonds, as modeled in Section 4. The $150–200 billion current-account improvement references the net reduction in the capital-account surplus once portfolio rebalancing is complete.