Making Sense of the Seemingly Nonsensical Mexican and Canadian Trade War

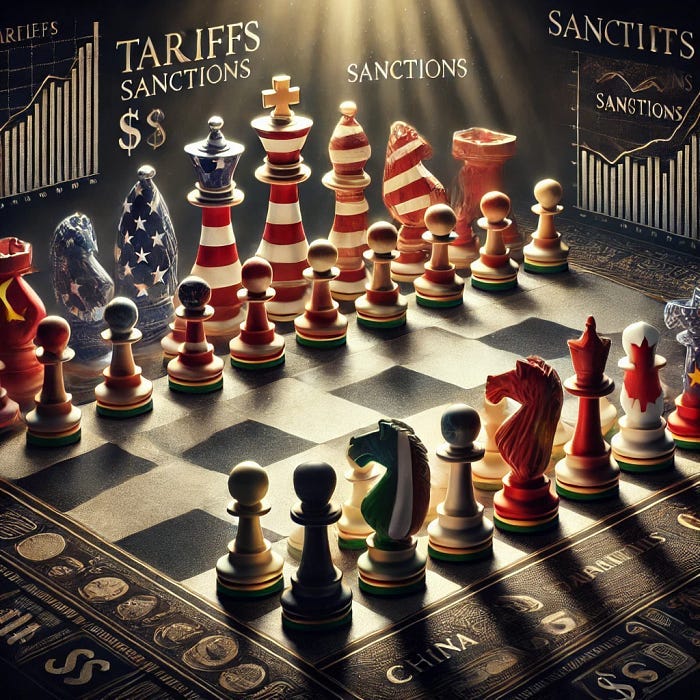

The Trump administration’s tariff campaign against Mexico and Canada seems inexplicable when viewed through the conventional lens of trade policy. While the administration has cited fentanyl trafficking as justification, this reasoning falls short of explaining such significant economic measures against key allies and trading partners.

A more compelling explanation emerges when we view these actions as part of a comprehensive strategy to restructure the global trading system.

The New Bretton Woods Gambit

What appears as erratic trade policy becomes coherent when understood as preparation for what Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent described before his appointment: “We’re also at a unique moment geopolitically, and I could see in the next few years that we are going to have to have some kind of a grand global economic reordering, something on the equivalent of a new Bretton Woods.”

Countries with persistent trade surpluses have built economic models around policies that suppress domestic consumption while subsidizing production and promoting exports. They have little incentive to voluntarily abandon their mercantilist strategies that have fueled their growth for decades. Without significant pressure, meaningful reform won’t happen.

Why Mexico and Canada First?

This approach serves two strategic purposes:

1. Establishing Credibility and Resolve

Many international observers believe Trump is bluffing — that when faced with domestic economic pain or market volatility, the administration will back down from confrontational trade measures. By targeting close allies first, even at considerable short-term cost to American businesses and consumers, the administration demonstrates it is deadly serious about restructuring global trade.

This credibility is the key to forcing surplus countries to the negotiating table. China, Japan, and Germany won’t make painful economic concessions unless they believe the alternative is worse. By demonstrating real willingness to endure domestic pain with Mexico and Canada tariffs, Trump is sending a clear message: negotiate or face unilateral measures with real teeth.

2. Strategic Preparation in a Lower-Risk Environment

Trade conflicts with Mexico and Canada represent a lower-risk testing ground for the administration’s trade war capabilities. These economies are more integrated with the U.S., more dependent on U.S. markets, and less able to inflict significant retaliatory damage compared to China or the EU.

This approach allows the administration to:

Observe real-time supply chain adaptations to sudden tariff changes

Identify which U.S. industries require special protection or support

Evaluate the effectiveness of countermeasures deployed by trading partners

Refine implementation procedures across government agencies

Develop playbooks for addressing specific economic disruptions

All of this builds institutional knowledge before confronting surplus countries with far greater capacity to retaliate and disrupt global markets.

The National Security Imperative Driving Military-Style Strategy

The Department of Defense’s influence on trade policy likely explains the “warm-up” approach. Military strategists have long understood the value of progressive engagement — you don’t send untested forces directly into the most challenging battlefield.

This military-style thinking makes perfect sense given the national security dimensions at stake. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte recently warned that Russia is outproducing all NATO members 4-to-1 in military supplies, with its economy now on a war footing. Even more concerning, China possesses more manufacturing capacity than the United States, Europe, and Japan combined.

The twin shocks of COVID supply chain disruptions and the Ukraine war exposed dangerous vulnerabilities in Western industrial capacity. Just as the U.S. began in North Africa before confronting the full might of Nazi Germany in WWII, the administration appears to be using the Mexico-Canada trade conflicts as preparation for the much larger challenge of restructuring economic relations with China and other surplus countries.

The Irony: Targeted Countries Could Benefit

Ironically, while Mexico and Canada are feeling the immediate pain of these tariffs, they could ultimately be among the biggest beneficiaries of a restructured global trading system. Mexico, with the 7th largest aggregate trade deficit globally, suffers from the same structural disadvantages as the United States in the current system.

Current arrangements harm all deficit nations, as capital flows from surplus countries inflate their currencies and undermine manufacturing competitiveness. Mexican producers, like their American counterparts, struggle to compete against economies that systematically suppress domestic consumption and maintain artificially weak currencies.

A new system with penalties for persistent surpluses and mechanisms to prevent currency manipulation would create a more balanced environment where Mexican manufacturing could thrive alongside American industries, rather than both losing ground to surplus countries that systematically suppress domestic consumption.

High Stakes Diplomacy

If successful, this approach could lead to a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” that reshapes global economic relations as fundamentally as Bretton Woods did in 1944. But unlike the Plaza Accord of 1985, which merely addressed currency values temporarily, this would seek structural reforms to prevent the systemically distorted trade and capital flows that have defined the past decades.

Even Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey recently acknowledged the need for systemic change, suggesting “a better alternative might be to change the arrangements put in place after World War II.” Bailey noted that the Bretton Woods system was “designed asymmetrically by the US so the adjustment occurs in deficit countries,” but “the US has ironically become the deficit economy.” While Bailey criticized tariffs as the wrong approach, his recognition that the multilateral system needs rethinking underscores the legitimacy of the administration’s broader goal.

The key challenge will be bringing surplus countries to the table for meaningful negotiations. These nations have benefited tremendously from the current arrangements and will resist changes that threaten their export-led growth models.

This is precisely why the administration is demonstrating its willingness to take unilateral action. Creating a credible threat of painful consequences provides the necessary leverage for productive multilateral negotiations.

What’s Next?

The tariffs on Canada and Mexico represent merely the opening gambit in a broader strategic campaign. Rather than viewing these actions as isolated or impulsive, we should recognize them as the first phase of a coordinated effort to restructure the global trading system.

The administration appears to be implementing a coalition-building strategy through calculated pressure. The terms are becoming increasingly clear: the U.S. will drop these tariffs only if Canada and Mexico explicitly agree to join in imposing their own tariffs against persistent surplus countries. This quid pro quo creates powerful leverage — exemption from American trade restrictions comes at the price of actively participating in a coordinated front against mercantilist economies. This approach paradoxically uses tariffs as a tool to force other nations into a collective effort aimed at achieving more balanced global trade.

For Canada and Mexico, the calculus is clear. Their economic integration with the U.S. makes resistance impractical. We anticipate both will ultimately align with American trade objectives against surplus countries, at which point the tariffs will be lifted and the administration will pivot to applying similar pressure on other trading partners.

As this strategy unfolds, expect continued aggressive trade measures, not just against traditional adversaries but potentially against all major trade partners. This tactic echoes strategies from the interwar period — a playbook largely forgotten today.

The fundamental challenge lies in achieving near-universal consensus among nations with deeply divergent economic interests. Meaningful restructuring requires bringing virtually every significant trading partner to the table, a diplomatic task of extraordinary complexity. Securing multilateral coordination on trade requires leverage, not just diplomacy. History is unambiguous on this matter. This reality, while uncomfortable, has been a consistent feature of every major trade realignment throughout modern economic history.

As events progress, the strategic coherence behind these seemingly chaotic actions will become more apparent. Trump isn’t uniquely targeting America’s neighbors — they’re simply the first stage in constructing what might be called a “coalition of the compelled.” Paradoxically, this confrontational approach may be the necessary catalyst for a more balanced global trading system.

Whether this approach succeeds remains to be seen, but the strategy itself is more coherent and far-reaching than most observers recognize. The current tariffs on Mexico and Canada aren’t the endgame — they’re just the opening moves in a much larger campaign.

excellent piece

Too much of the media suffers from TDS, I wish the NY Times had more articles like this.